A few follow-up notes to some things we discussed recently:

First, this article from Scientific American called, “Long COVID Now Looks like a Neuorological Disease,” which addresses some of the points back here in my post about my concerns about COVID and suicide. They talk about inflammation and other brain-based COVID matters, if you’d like to take a deeper look at the emerging science.

Second, if you haven’t seen it already, I encourage you to brace yourself for the inclusion of new AI tools at work, specifically if you’re a user of Microsoft Office 365. You can read through all of the features (including the creepy ones) here. Here’s the link back to our ChatGPT episode; when I said the robots are here, I wasn’t joking!

Finally, I’ve been thinking more about my comments last time related to Gen Z and the idea that they’re not gonna take any nonsense from orgs, and I had a thought about it.

My initial framing is that economic formative contexts drive some of their views of their relationship with employment and employers, but I forgot one thing that I think could also be relevant, especially here in the wake of Yet Another Shooting in an Educational Environment last month:

GenZ is the Active Shooter Drill generation. I have always felt that living through that context would mean higher levels of anxiety for students in the classroom even beyond K-12, which obviously concerned me as an educator since anxiety and learning cannot peacefully coexist.

But I failed to recognize how potentially potent the School Shooting context could be for people’s relationships with authority and with institutions. I imagine their interior monologues:

It’s clear you don’t care about us, right? You continue to allow us to be sitting ducks in our own classrooms in the institution of education, refuse to address the heart of the issue, use these incidents to push more carceral and surveillance arrangements in schools and society, and continue to offer vapid and empty commentary.

If I were them, it would be very clear to me that no one will prioritize me except me. Therefore, occupying space that doesn’t suit me or satisfy me will not be a way to spend my time. I also wouldn’t be afraid to take on authority in the workplace, especially around abusive policies or other things that simply don’t make sense, rules that apply to a world that no longer exists.

I was thinking about this situation as I read another first-hand commentary about how different GenZ is in the workplace. They aren’t necessarily adhering to the unwritten rules of professional behavior, like “don’t take a sick day” and “make sure your boss knows you give 110%.”

It’s so easy to see the BS in orgs when part of the routine calculus in one’s life has always included a backtrack wondering, “Am I gonna be gunned down as I sit in this seat?”

Personally, I’m here for it. Those rules are outdated, rife with biases and performativity, and literally how some of the the worst people end up in seats of power and authority. Burn it down, I say. I can’t wait to see the org lit on these dynamics in the future.

Now, onto our regularly scheduled content.

Thank you, IHE, for posting an article that prompted me to finally finish up one of these drafts sitting in my queue because I have some info to add to the recommendations contained therein: Seven ways to leverage faculty development for student success, recommendations from Achieving the Dream.

I appreciate the conversation about faculty development (what ATD calls professional learning) in light of how college faculty are and are not students of pedagogy. Some people are: Some people had formal pedagogical training as part of their degree programs, but many of us have not.

Many of us started our careers teaching how we were taught, and often, that worked for us.

It doesn’t always work for many students, though, and as many of us started seeing that reality, we took on pedagogical innovation on our own1. One thing I like to remember is that I’m a survivor of higher ed: I am here in this seat because the traditional approaches worked for me (I mean, barely), but I’m an exception in many cases, not the norm. My students are not always like me in many ways.

I’m also a super nerd who cannot tolerate my own ineptitude. I’m fine being bad at karaoke. I do that once every five years, tops. I’m not fine being bad at anything I do routinely, from parallel parking to cooking to my job.

If I’m gonna do it, I’m gonna do it well, and that’s what launched me into my own investigation of the art and science of teaching. I had been introduced to the fundamentals of teaching and learning prior to starting my career and had a natural inclination toward teaching2, but I took a focused approach to developing my knowledge and skills because — again — if I’m gonna do something, I’m gonna do it in the nerdiest and most academic way possible, by going to the research, hypothesis testing, analyzing data, lather, rinse, repeat.

I also sit in spaces, though, where the discourse is such that I’m always left feeling like nothing is ever good enough, fast enough, effective enough, inexpensive enough.

I’ve reached a point where I internalize that less and situate those dynamics external to myself for the most part, but I can’t deny that I’m affected by those waters. Imposter syndrome, some might say, but I don’t think that’s a thing, really. Personally, I think it’s just toxic water, and even healthy fish can’t thrive in it. I also think it’s pretty common across higher ed, to be honest.

So perhaps some of us have twisted internal motivations for innovation, but I have also spent years thinking about and investigating how learning and development actually happens in orgs in terms of the systems and structures that undergird the entire process.

I had been drafting something about pedagogical innovation here in the newsletter and then conveniently, that IHE article summarized Achieving the Dream’s recommendations for faculty development to support student success.

Let’s talk about ATD’s recommendations, and I’ll fill in with some additional contextual considerations and operational matters, loosely based on my own research but also recommendations from a new book by a Danish economic geographer on getting big things done because that framework can be useful here.

Here are the seven strategies from ATD:

Engage3 all instructors—including part-time faculty—in professional learning and as partners in change.

Design sustained programs such as faculty learning communities that yield improved teaching and equity outcomes.

Assess the impact of professional learning. Move beyond head counts and correlating participation with changes in practice and student outcomes.

Develop a strategic vision for a CTL (Center for Teaching and Learning). Ask where it should be in three to five years and then plan how to get there.

Invest in CTLs.

Strategically deploy faculty development in support of mission-critical initiatives, including those related to enrollment, retention and completion—especially at community colleges and MSIs

Demonstrate commitment to teaching improvement. Leverage faculty reward systems to recognize engagement and power cost-effective teaching improvement efforts.

First, a major shout-out to the CTL people among us. I don’t think our colleagues in CTLs have yet recovered from the demands placed upon them in 2020, I really don’t. Hats off to all of you, really, and sincere gratitude for all that you did at your various orgs to fill in the gaps and to provide much needed expertise and support as faculty transitioned to remote learning.

One disclaimer, though, as you’re reading through those recommendations above, especially on the CTL advice:

As important for Centers for Teaching and Learning are, I want to make clear here that you don’t necessarily need to build one if you can’t do that: Most orgs probably can’t whip up the budget, but I think that even if we can’t create a center for teaching and learning, we can certainly create a culture that supports ongoing improvement in teaching and learning.

I want to add some color to the ATD recommendations because my research on innovative pedagogy gives them legs while also adding considerations for the context in which these activities live. I’ve interviewed faculty about their deployment of innovative practices, and more recently, I’ve read a text from a researcher I really like: Dr. Bent Flyvbjerg, the Danish economic geographer I mentioned earlier.

I’ve learned a lot reading Flyvbjerg’s work, especially in light of his research on power and rationality (big note: More power = less rationality).

Anyway, it just so happened that I was finishing up a Flyvbjerg (and colleague, Dan Gardner) book called How Big Things get Done: The Surprising Factors that Determine the Fate of Every Project as I was finishing up the ATD report on professional learning. I think Flyvbjerg’s work is relevant to this conversation.

His book is a fascinating look at what happens in big projects. Did you know, for example, that 99.5% of big projects (think IT, buildings, bridges, tunnels, etc.) exceed their budgets or schedules or under-deliver on promises in some combination?

We might think, yeah, of course: But NINETY NINE POINT FIVE PERCENT OF THEM? Flyvbjerg says, “It’s hard to overstate how bad this record is.”

Like, statistically, it doesn’t even make sense to me. But here we are.

The dynamics of Flyvbjerg’s analysis apply to smaller projects, too, so he outlines steps to avoid the biggest pitfalls in execution. We can learn some things as we take on projects like professional learning.

He lays out eleven heuristics for big projects, and I’ll focus on a few that I think are most crucial to building capacity for pedagogical innovation at scale.

Expertise

Even in environments where we want a broad base of inclusion and a spirit of egalitarianism, we need what Flyvjberg calls a master builder, someone with “deep domain experience and a proven track record of success in whatever you’re doing.”

In thinking about professional learning, I recommend two master builders: First, someone with deep knowledge in the art and science of teaching and learning, not just theoretically but practically.

We want someone (or a group of someones) at the edge of innovation, always scanning the environment for recent developments in teaching and learning, unafraid to try, test, and try again (generally, people who are secure in the environment by virtue of tenure or other protections. Not everyone can safely take risks).

In a professional learning situation, we have two dynamics unfolding, two prongs of learning:

We have the discussion of actual teaching and learning strategies that we’ll deploy in the classroom learning context (whatever that is: Virtual, F2F, etc.) but also the actual learning of the participants. So we’re talking about the teaching and learning of students but also the teaching and learning of faculty.

Someone needs oversee that second part of the learning because if my fellow educators sit through one more learning experience designed by people who don’t actually teach, it’s not gonna be good.

In other words, we want the people who do the work at the head of this project, and we need people who are trusted and recognized as experts within the org context. Not everyone will be a good driver for the innovation bus.

Pro-tip: Orgs don’t do a good job of measuring trust, and the construct of trustworthiness rests in the eyes of the beholders. People with power might think they know something about who is trusted, but as Flyvbjerg points out, power reduces rationality. We need an actual analysis here to help in the determination.

We also need a good administrator — your second master builder — someone who can procure resources and eliminate barriers, organize and coordinate schedules, and handle any nonsense bureaucracy with grace and charm. They need to be good relationship managers, too. (Related literature: Distributed leadership to support professional learning.)

Ideally, they’ll also have a research vocabulary because someone will need to pull and organize some data. Your cutting edge faculty can develop some research questions, and a good administrator can work with the research office to gather that data in meaningful formats.

If you have one person who can fit the bill of both master builders, good for you. I hope you are protecting (and paying!) that unicorn at all costs. But if you aren’t that lucky, job one is to figure out how you’ll manage the need for deep domain experience, a high level of trust, and expert project and relationship management.

External Engagement

Flyvjberg is funny on this point: He says, look buddy, whatever you’re doing or trying to do has been done before. You’re not engineering a black hole. So go find the people who already did it well and ask them how they did what they did. He’s right!

But let me speak the language of organizations for a minute:

Organizational context matters because pedagogical innovation can be easier to do in a teaching-focused environment. SLACs, CCs, etc. are well-positioned to talk pedagogy because it’s what we do all day every day; we’re literally hired to be good teachers. Research-focused orgs? Not always the same animal. Thus, careful consideration of local factors must be part of the discussion because each ecosystem requires its own kind of approach.

Nothing good will happen without an environment of trust. If you’ve heard me talk about change before, you know that trust is literally the foundation for effective change of any sort, and that includes ongoing analysis of our own teaching.

One reason talking about teaching improvement is challenging is that it hits at fundamental parts of our identities: Many of us think we’re good people doing good work, and many of us were good students. We want to do the right thing in the right way, and evidence to the contrary hits us right at the heart of who we think we are.

Part of the reason trust is such a huge variable in this conversation, especially, is that pedagogical innovation requires safety because the process requires trial and error. There will be failures. But when faculty feel safe to experiment, take risks, and share both success and failures, innovation can thrive. We can create a cycle of ongoing experimentation and improvement.

What I like about the idea of external engagement is that I always want to know the theories of change behind what successful orgs have done: Why did you think X was gonna work? What theories drove your decision-making? I want to know where they situated their plans, theoretically speaking, because success — as we’ll see in a moment — is often the result of slow and careful planning.

Execution

Flyvjberg’s bias is toward planning: He spends a good chunk of time and space supporting the value of slow thinking and fast acting: He turns the tech-bros’ “move fast and break things” paradigm on its head, and for good reason (see the failure rates above!).

Basically, he says we should spend time figuring out what we want to achieve and WHY, and from there, consider taking a modular approach to achieving our aim: Think long and hard, and then move small parts ahead.

Pedagogical innovation is much different from building a social media network or a bunch of earthquake-proof schools in Nepal (one of Flyvjberg’s projects: 20,000 schools!), but we can use the same approach: The team built one classroom at a time, and they came in way under cost as measured in both time and money.

We can take this lesson and use it as we approach professional learning, building capacity one small team at a time. Conversations about pedagogy almost always start with the choir members, the people who are already attuned to good teaching and learning. Giving them time and space can help us expand the reach of these conversations. Dr. Karen Stout at ATD is clear about that:

For faculty and staff to really focus and reflect on their practice, they need professional support, as well as the time and space to do so.

Flyvjberg makes a great point that small is good: “Pedagogical Innovation” at scale is one huge thing. We need not approach it as such, though, because this type of change is a rolling one: When small teams try something, refine, and try again, we experience positive learning, a dynamic that creeps out as people share their results with others in the org.

Imagine, for example, that a cross-disciplinary group of faculty is working on pedagogical innovation, testing out new ideas and reporting back to the group. When they share their experiences with their home departments, we’ll likely see others take up similar ideas, test them out, and try again.

The modular approach can help us achieve something big through a focus on the small.

(Bonus content: Execution should include ideas from Dr. Cate Denial’s grant-funded work on care in the academy. Here’s an excellent introduction to how we can build capacity for care in meetings and figure out the WHY (note that goals are different from purpose), ideas that should guide this specific work of faculty professional learning. I read the Dean Spade book she mentions, and I highly recommend it.)

Where to Start?

For many orgs, outcomes for minoritized students (race, SES, disability status, citizen status, etc.) lag. The place to begin this process is with a deep data dive: You might remember my recommendation that we disaggregate our course data all the way down to the section level to see what’s working and where (in fact, that whole post sort of lays out a plan).

This step helps us identify the problem we’re attempting to address with professional learning. What, exactly, are we trying to learn and why?

Once we do that, we can work on targeted approaches and focus our innovations accordingly. In that linked post, I also make the recommendation to involve students: Too often we talk about students and around students as we build strategy; including them in the discussion about teaching and learning is a smart way to research what’s happening on the ground.

In my dreams, orgs call me to conduct focus groups with students about their classroom experiences and compile a roadmap of what’s going well on the ground along with opportunities for future development. Seriously, call me. Let’s do this.

(Alternately, you can just use your internal resources to do it. Faculty with trusted peers can engage in this process on their own.)

That sort of data analysis leads us to what we want to do and why. We’ll want to situate the work theoretically, locating evidence of what works in solving the problems we want to solve in student success and designing a plan that fits our context.

We’ll also want to situate the work of faculty professional learning theoretically, locating evidence of what works in professional learning and designing a plan that fits our context.

(These are the two prongs I mentioned earlier.)

But part of the whole thing, really, involves acknowledging some contextual realities about this conversation that can’t be ignored. The linked article is about A.I. but asks if higher ed is too rigid to save itself. I wonder the same thing about pedagogical innovation, to be quite honest. Can we devote the time and resources to thoughtfully considering our changed contexts and to building a new future? It’s a good empirical question.

At the end of it, though, these suggestions from ATD coupled with a heavy dose of contextual consideration and advice from Flyvjberg on Big Things can help orgs flex to meet the needs of our current and future students and build capacity for ongoing innovation.

I don’t love using pedagogical innovation because it seems so lofty when, really, so much of good teaching comes down the sum of small decisions. I like James Lang, Small Teaching, on this point.

By engage, let’s mean PAY.

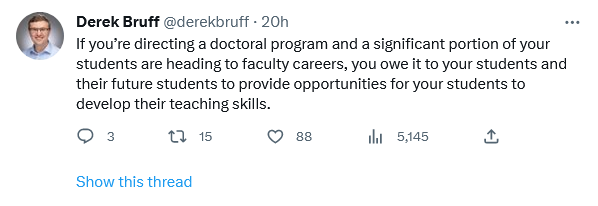

Faculty Professional Learning