I’ve shared before that I think a lot about operationalizing our terms in organizations: What does respect mean, for example, and how does it look in practice? How does the definition change depending on positionality? On context?

I’m grappling with operational definitions as I sit in an org that has centered “care” in its next strategic plan.

Admirable! Laudable! And obviously I agree with the approach, having written about this very thing.

But….what does it mean? That’s where I need help: What is care to you? If your org said, “We are centering care in our environment,” what meaning would you make out of that? How would “care” look to you in practice?

Here’s why I’m asking:

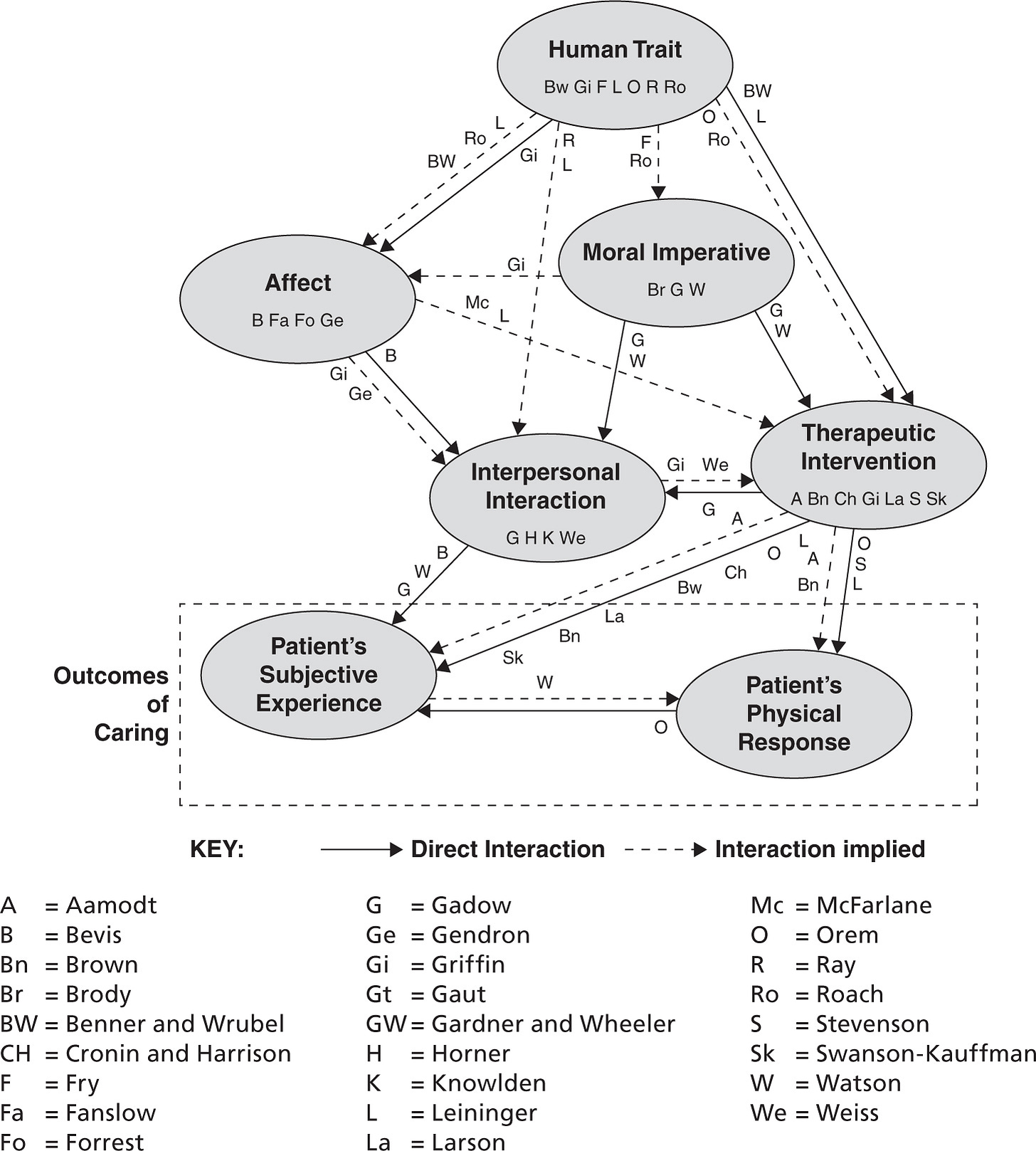

Care is not apolitical and brings with it some inherent questions: Care for whom and by whom and in what context? We have a whole body of literature about care, and care is a complex, contextually-bound (and power infused!) construct. Take a look at this image from a nursing text, for example:

Organizations are wise to define exactly what they mean when they talk about care, especially, because care is not built into the bureaucracy.

Efficiency, yes.

Hierarchy, yes.

Rationality, yes.

Formality, yes.

Care? No.

And I contend that efficiency, hierarchy, rationality, and formality are in direct opposition to care. Care takes time, violating the value of efficiency in the traditional sense. It requires attention to power matters. Care violates the principles of rationality (in the bureaucracy, rationality means that activity is driven by impersonal rules for the sake of efficiency). Care violates formality by centering subjectivity.

Care also creates a conflict because of the neoliberal waters in which higher education swims (too many sources to link but some important ideas here)1.

Hence, orgs need to reject some values of the bureaucracy and of neoliberalism if they plan to embrace the value of care. Like, explicitly reject them. Otherwise, conflict will emerge swiftly as constituents wonder, “How does this decision demonstrate care?”

Values statements in organizations are promises, and it’ll be quickly apparent when promises aren’t kept. Thus, operationalization cannot be left to chance.

My fear, ultimately, is that some in an org will operationalize care as simply focused only on students and only on micro-level interactions (1:1), an interpretation that brings with it a host of trouble.

If care for students means that everyone else in the environment is to grind themselves to the bone in the name of care, well. That’s not a sustainable approach. Care is easily weaponized, and care expectations are not evenly distributed in an organization. From Lorna Campbell:

Caring has always been regarded as women’s work, and as a result, the labour of caring is habitually devalued and taken for granted. There is an assumption that caring is low skilled work, that anyone can do it, but of course that is far from true.

Further, a focus on care may be intended to drive micro-level interactions as opposed to system-level matters and to me, this dynamic is problematic and also at the center of organizational struggles around inclusion:

Orgs often relegate the idea of inclusion to the micro without changing the structures and policies in which those micro-level interactions live. If we say we value “inclusion” or “care,” for example, we need to infuse those values across all levels and reject the other values built into the bureaucracy that are at odds with what we want to achieve2.

I’ll use an example from the commercial world to illustrate what I mean:

Org A has decided it wants to embrace “community” as a driving value. Great! What they mean is that “we create a professional environment where teams are interdependent in their work, where success for all is prioritized, and where we feel connected to one another in positive ways.” Tactics include the following:

They host pizza Fridays, integrate community-building platforms like Slack into their workflow, and intentionally bring teams together to create community.

They make on-site work meaningful: While people mostly operate remotely, they come together one time per week in the same space, and that time is spent in meaningful on-site interactions, not on remote platforms.

They (implicitly) reject efficiency for the sake of relationship-building, giving team members time to interact with one another without the pressure of constant, traditional productivity. In other words, they see interpersonal relationship building as productive.

They’ve also built in periodic measures to gauge employees’ sense of community in the workplace.

Wonderful, great job, love it.

But at the same time, they haven’t changed their compensation and promotion structure: Both are still focused on individual performance instead of team performance, which drives individualistic behaviors that are at odds with the purported goal of community and the idea of interdependence.

The policy drives the practice. And since this org hasn’t operationalized its value of community at all levels, the metrics haven’t shifted on “employee sense of community” at all.

They haven’t explicitly rejected the value of “individualism” baked into the bureaucracy (baked in because it’s baked into Western cultures, and orgs typically replicate the dynamics of the waters in which they swim).

When thinking about care, then, it’s important to operationalize. What happens, for example, when care needs are in conflict with the efficiency demands of the bureaucracy? Caring for and about people in the org requires time.

Lofty, progressive goals and values are GREAT. I wish more orgs would center care, for example, in their decision-making3.

It’s not enough, however, to say we’re doing it; we need to interrogate every level of activity — from the micro on up — to operationalize our terms, identifying points of conflict and a process for resolving those conflicts.

Because if we’re gonna say we’re doing it, people like me are gonna demand that we actually do it, even when it’s not easy. I’m with Hamilton Nolan, who writes in this month’s In These Times that the radical is now rational. He’s talking politics, but the sentiment holds for orgs, too:

It’s not a question of what is easy but of what is necessary. If something is necessary, we must do it even if it is hard. The consequences are too dire to be a reasonable choice.

How does care look to you in higher education?

Some might suggest that this discussion is far too pedantic, but my argument is that one reason change efforts in organizations often fail is that we aren’t pedantic enough. We often use language with assumptions that everyone knows what we mean and understands how to operationalize concepts, but those assumptions are incredibly flawed as evidenced by how often orgs are unable to meet their goals and how often we have the same conversations over and over and over again. Clarity wins the day, every time.

No better example than this one, in the news as I’m writing this. Basically, we want to say we’re “inclusive” but how orgs often interpret that idea is that we’ll allow you to be here, but we won’t change anything about what we do in order to meet your needs. For me, that’s due to the values of inclusion butting up against the priorities of the bureaucracy. It’s in no way efficient or rational to meet individual needs, and even when required to do so by law, orgs will often find the cheapest, fastest, and easiest pathway, one that’s often inherently exclusionary. Doing the right thing is rarely cheap or easy.

Something else I’m thinking over is how the measurement of care unfolds. In a setting like higher ed — where these days only that which is quantifiable seems valued — how does care remain a priority? I don’t know that the ground is fertile enough to grow that flower.